Third Text

- Thinking Gaza: Critical Interventions

- Living Archives

- Decolonial Imaginaire

- Decolonising Colour?

- ‘Artist and Empire’ Part 2: Singapore (2016–2017)

- ‘Artist and Empire’ Part 1: Tate Britain, London (2015–2016)

- Emilia Terracciano, ‘Dispelling the Myth of the “Positive Legacies” of Empire’

- Renate Dohmen, ‘All Bark and No Bite: India at Tate Britain’s “Artist and Empire” Exhibition’

- Natasha Eaton, ‘Tired Ornamentalism’

- Nicola Gray, ‘Echoes of Empire: “Artist and Empire” at Tate Britain’

- Louis Allday, ‘On (Not) Facing Britain’s Imperial Past at Tate Britain’

- Jessyca Hutchens, ‘Ambiguous Narratives: “Artist and Empire” at Tate Britain’

On (Not) Facing Britain’s Imperial Past at Tate Britain

Louis Allday

In a country where public discourse concerning the actions and legacy of the British Empire is principally shaped by the likes of Dan Snow, Jeremy Paxman and Niall Ferguson, any cultural event that seeks to critically assess Britain’s imperial history is not only welcome, but crucially necessary. So, after I saw the sub-heading of Tate Britain’s latest major exhibition ‘Artist and Empire: Facing Britain’s Imperial Past’,

I was intrigued and cautiously optimistic that it might be the start of a move away from the wishy-washy apologia of Snow, Paxman’s nostalgic glorification and Ferguson’s transparent adoration of imperial power towards something more honest and critical. My hopes in this regard were raised further by a glance at the selection of books for sale in the exhibition shop on the day that I visited, for, although the ubiquitous histories of the British Empire by Paxman and Ferguson were unfortunately there, so were C L R James’s crucial studies A History of Pan-African Revolt and The Black Jacobins, Edward Said’s Culture and Imperialism (although strangely not his classic work, Orientalism – more on that later), Richard Gott’s Britain’s Empire: Resistance, Repression and Revolt and Franz Fanon’s seminal works Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth. The limited edition ‘Empire’ India Pale Ale that I also spotted for sale seemed distasteful, but I hoped it was not a sign of things to come.

The introductory text of the exhibition, printed on the wall next to its main entrance, states that the British Empire’s ‘history of war, conquest and appropriation is difficult, even painful to address’. Of course, it is a history that the Tate itself is intimately entwined with. As observed by historian Andrea Stuart, ‘thousands of locals and tourists visit the grand Tate Galleries without remembering that its collections were funded by the exploitative sugar company Tate & Lyle’.1 Unfortunately, it appears that ‘facing’ this past ultimately proved too painful for the exhibition’s curators; anyone hoping that this exhibition engages critically with Britain’s imperial past will be left largely disappointed. There is no doubt that the exhibition brings together a number of fascinating, visually arresting and thought-provoking objects (the beautiful watercolours of the Indian artist Shaikh Zain ud-Din were a personal highlight). However, as I made my way around the exhibition I quickly felt a sinking feeling as I recognised the familiar pattern of quasi-glorification, carefully non-committal wording and vague explanations coupled with a distinct lack of open, critical analysis of the realities of the British Empire. As observed by Richard Gott, the British Empire was ‘established, and maintained for more than two centuries, through bloodshed, violence, brutality, conquest and war’.2 From the perspective of the majority of those colonised, aside from a small elite, the experience of empire was one of seemingly never-ending brutality, racism, dispossession and subjugation. Admittedly, acts of violence on behalf of the British Empire are explicitly acknowledged in the exhibition, but they are only mentioned in passing and never from the perspective of the victims. On the contrary, Britain’s violence is often rationalised and most worryingly, occasionally appears to be tacitly justified. Much like the way in which in contemporary media parlance, Israel appears to permanently be ‘retaliating’ against the ostensibly violent and irrational Palestinians, the British Empire is frequently portrayed as merely reacting to the violence of the ‘natives’.3 This problematic tendency is encapsulated perfectly in the choice of wording for the caption of two of the exhibition’s most stunning pieces; two bronze head sculptures from late nineteenth-century Benin (two of the famous ‘Benin Bronzes’). An extract of the caption for the heads reads as follows:

These heads were among the many precious ancestral objects looted from the palace of the Oba (king) of Benin during a British ‘punitive raid’ in 1897, in retaliation for the killing of envoys trying to negotiate trading rights.

Therefore, in the same sentence that it is introduced, the killing of the ruler of Benin’s capital and subsequent looting of precious artefacts on an enormous scale is immediately rationalised and presented as merely ‘retaliation’ on behalf of the British. The official vocabulary of a ‘punitive raid’ is repeated uncritically and the crucial background – that the invasion of 1897 was in fact motivated by Britain’s long-standing desire to destroy one of the last independent kingdoms in the region and gain access to its plentiful natural resources of palm oil, rubber and ivory – is entirely obscured.4 The broader context, that the Kingdom of Benin’s destruction took place at the height of the so-called ‘Scramble for Africa’, during which European nations ruthlessly conquered and divided up the African continent between themselves, is also left unmentioned. The specific incident to which the caption refers, the so-called ‘Benin Massacre’ of 1897 was not the cause of the Kingdom of Benin’s demise, but merely the spark that provided the British with the pretext needed to launch an all-out invasion against the Kingdom and thus complete its takeover of the region. Moreover, the ‘trade envoys’ mentioned in the caption were in fact a large contingent headed for the capital, composed of a number of British military officers, two trading agents and a group of 250 native porters, servants and guides. The force was also accompanied by a drum and pipe band and, as Ian Hernon has observed, ‘a column of that size suggested military intent’.5 Subsequently, the group was mistaken for an invading force and after calling a national emergency, the Oba sent a force of tribesmen from all over his kingdom to move against it.6

The Benin bronzes appear in the exhibition’s second room, which is titled ‘Trophies of Empire’. In the three paragraphs of explanatory text provided for this room, the central role that systematic looting and plunder by the British played in the accumulation of so-called ‘trophies’ is drastically underplayed. The text states that ‘loot, barter, gift and purchase by soldiers, sailors, explorers and missionaries all contributed to the Empire’s collection’. This single mention of ‘loot’ is the only reference to the central role that violence played in the accumulation of such ‘trophies’. The widespread practice of the collection of human remains including skulls and other bones (not to mention the shameful, but not uncommon phenomenon of human zoos) is not mentioned at all.7 Of course, Britain’s looting was not limited to West Africa, it was so rampant in India, for example, that the word ‘loot’ itself is actually derived from the Hindustani slang word for plunder, but this too is not mentioned. Ironically, the caption for a Mughal miniature painting in this room states that ‘Mughal paintings were sought after by elite British collectors in India’ yet makes no mention of the widespread looting of Mughal paintings and other artefacts committed by British forces, notably after the Indian Rebellion of 1857. In September of that year British forces assaulted Delhi (with orders to ‘shoot every soul’) and during the subsequent sacking of the city, the Mughal’s grand library in the Red Fort was ransacked and its contents shipped almost wholesale back to Britain.8 The British Library now holds this collection, one so huge that it is yet to be fully catalogued, over a hundred years later. More broadly, looting committed by the British in India was so vast in scale that Powis Castle (in Wales) alone holds more Mughal artefacts ‘than are on display at any one place in India – even the National Museum in Delhi’.9 William Dalrymple has observed that in the late Victoria era, motivated by embarrassment at the ‘shady’ mercantile origins of the Empire in India, a ‘calculated and deliberate amnesia about the corporate looting that opened British rule in India’ took place. It appears that for some this amnesia is ongoing; to imply that legitimate purchase and barter played an equally important role as plunder in the acquisition of ‘trophies’ is wholly inaccurate.

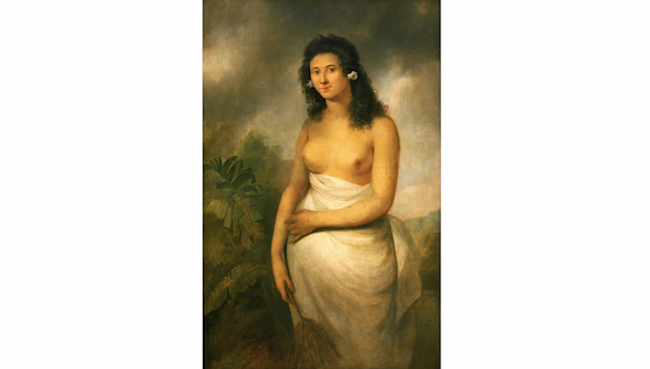

John Webber, Poedua, the Daughter of Orio, 1784. Oil paint on canvas. Support: 1454 x 959 mm. Frame: 1675 x 1170 x 100 mm. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

Another room in the exhibition is titled ‘Face to Face’ and focuses on depictions of the colonised produced by the colonisers and vice-versa. Bizarrely, 'Orientalism' is not mentioned at all in any of the wall texts in this section. Rather, the introductory text patronisingly states that ‘sometimes, British observers romanticised people they saw, or found them mysterious or troubling’. Whether it was an intentional choice, or an oversight, on behalf of the curators, to not engage whatsoever with the substantial body of work that discusses the manner in which the colonial ‘other’ was portrayed in Orientalist art is a major and frankly, quite remarkable omission. This is notable given that Orientalist projections, so frequently tied in with the political objectives of empire, were conceived by Said et al as overtly political. One of the most striking pieces in this room is John Webber’s work Poedua, the Daughter of Orio, a large portrait that depicts a bare-chested woman, Poedua was the nineteen-year-old daughter of Orio, chief of one of the Society Islands around Tahiti. In the caption for the portrait, it is stated that the painting was based on studies made by the explorer James Cook, while he was ‘keeping her [Poedua] hostage in his cabin’. The disturbing implications of a young female hostage being held in Cook’s cabin and subsequently depicted half-naked in a portrait are not acknowledged or explored any further. On the contrary, and just as in the wording of the caption for the Benin Bronzes, Cook’s act is tacitly justified. Poedua’s imprisonment is explained away as necessary ‘to guarantee the safe return of several crew members who had jumped ship’.

The language used throughout the exhibition is measured, plain and un-emotive; words like violence and racism are rarely used and in the introductory text, the term empire itself is described oddly as being ‘provocative’. A notable exception to this tendency is the way in which violence committed against the Empire is described. The British Empire was responsible for countless massacres and outrages, yet the only massacre that is explicitly mentioned in the exhibition is that of the killing of British civilians at Cawnpore during the Indian rebellion of 1857. In the caption for Joseph Noel Paton’s famous work In Memoriam, this incident is described as a ‘slaughter of women and children’ and ‘the most notorious atrocity associated with the Indian rebellion’. In the same sentence it is noted that it provoked ‘bloody reprisals’, but no details of these reprisals (which involved the killing of large numbers of sepoys [infantry private] by ‘blowing from a gun’ – a method of execution in which the victim was tied to the mouth of a cannon and the cannon was then fired) are given. The incident is mentioned again in the caption for Edward Armitage’s painting Retribution (1858) and described as a ‘massacre of women and children’. The context of this violence and the Indian Rebellion more broadly are not given in either caption. Both of these paintings appear in the exhibition’s third room, ‘Imperial Heroics’. The introductory text for this section notes that few of the works in the room show the ‘social upheavals and unequal power relationships which the rhetoric of Empire sought to gloss over’. It is very revealing that the curators of the exhibition had no hesitation in describing a massacre committed against the British as a ‘massacre’ more than once, but when discussing the violence committed by the Empire itself, slaughter and devastation become simply ‘social upheavals’ and the slave trade, forced labour and colonial subjugation are termed merely ‘unequal power relationships’.

This is a black-and-white reproduction of Blowing from Guns in British India, a painting created by Vasili Vereshchagin in the 1880s. This particular reproduction was used in 'Raubstaat England', a 1941 anti-British propaganda leaflet issued by the Nazi Government.

The exhibition’s introductory text states that it ‘foregrounds the peoples, dramas and tragedies of Empire’. Yet, tellingly, the only subsequent mention of ‘tragedy’ that I could see in the entire exhibition did not refer to any one of the manifold tragedies that befell those colonised by Britain but rather a crushing defeat of the British Army in the first Afghan War of 1839–1842. In the caption for Elizabeth Butler’s Remnants of an Army, the retreat of British forces from Kabul, in which the majority of British troops died, is described as a ‘tragic episode’. Once again, the actions of the British are explained away in the caption’s text, with the British occupation of Kabul described as being carried out with the aim of ‘protecting British India’ from the threat of the Russian Empire to the north.

Elizabeth Butler, The Remnants of an Army, 1879. Oil paint on canvas. Support: 1321 x 2337 mm. Frame: 1780 x 2790 x 226 mm. Tate Collection.

As I made my way around the gallery, I noticed that the predominately white, affluent-looking visitors were responding positively to it. Of course, there is nothing wrong with showing interest in (or amusement at) an exhibition, notably one that is based around art and artistic developments. But if the British public are to ever ‘face’ the country’s imperial past honestly and constructively, an exhibition that makes us feel distinctly uncomfortable (if not ashamed) rather than passively interested is what is required, however ‘painful’ that may be.

1 Andrea Stuart, Sugar in the Blood: A Family’s Story, Portobello Books, London, 2012, p 375

2 Richard Gott, Britain’s Empire: Resistance, Repression and Revolt, Verso Books, London, 2011, p 1

3 Greg Philo and Mark Berry, Bad News from Israel, Pluto Press, London, 2004

4 Thomas Uwadiale Obinyan, ‘The Annexation of Benin’, in Journal of Black Studies, vol 19, no 1, September 1988, pp 29–40

5 Ian Hernon, Britain’s Forgotten Wars: Colonial Campaigns of the 19th Century, Sutton Publishing, 2003, p 410–411

6 Some online sources claim that the party was in fact a military expedition undercover, which was attacked before hidden arms could be accessed – this could not be verified.

7 This shameful legacy is examined through the work of the artist Judy Watson in the exhibition’s final room ‘Legacies of Empire’.

8 William Dalrymple, ‘A dynasty crushed by hatred’, in The Telegraph, 1 October 2006, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/3655677/A-dynasty-crushed-by-hatred.html

9 William Darlymple, ‘East India Company: The Original Corporate Raiders’, in The Guardian, 4 March 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/04/east-india-company-original-corporate-raiders

‘On (Not) Facing Britain’s Imperial Past at Tate Britain’ was first published on Louis Allday’s blog 'The 36th Chamber' on 16 January 2016. Allday is a doctoral candidate at the Department of History, SOAS, studying British Cultural Propaganda in the Middle East. He is also a Gulf History/Arabic Language specialist working on a digitisation project at the British Library.

Download: On (Not) Facing Britain’s Imperial Past at Tate Britain